Soft Zeros

29 Nov 2025 - 2 Feb 2026

solo exhibition

Secession, Vienna AT

MOMA R&D Salon 56

Jan 20 2026

Museum of Modern Art, NY USA

Ohio State University Visiting Artist

2025 - 2026

solo presentation

Wexner Center for the Arts

The Columbus Museum of Art

OSU (various locations), Columbus USA

current

selected works

Ground Truths, 2025

Single-channel 4K video

15:59 minutes

In 2018, the remains of 95 people were discovered in a mass grave in Sugar Land, Texas. All were casualties of convict leasing, a 19th and 20th century system in which mainly Black Americans were often charged with false or trumped up crimes so their labor could be sold to the highest bidder. Artist Mimi Ọnụọha grew up minutes away and, like most in her hometown, had no idea the grave existed. One question haunted her: how did no one know?

In Ground Truths, Ọnụọha builds a machine-learning model capable of predicting where other such graves lie hidden across Texas. But the deeper she goes—through archives, phone calls, missing records—the more the project destabilizes.

What emerges is a portrait of human and structural forgetting: absence as infrastructure, silence as inheritance, data shaped by the gaps that inform it. The docufiction film asks what happens when the tools we trust to reveal truth are built from the very systems that produce erasure. Ultimately, this is a film about what constitutes our ground—the foundations of knowledge we inherit, what they conceal, and what remains buried beneath them.

No One Told Me, 2025

Site-specific installation,

custom boundary tape

No One Told Me consists of custom-printed barrier tape installed throughout the exhibition space, physically cordoning off areas and directing visitor movement. The tape bears nine phrases—"no one told me," "how could I have known," "it's not my history," "get over it," among others—that range in tone from seemingly innocent deflection to dismissive hostility.

These statements of deniability function both architecturally and conceptually: as the tape restricts physical access within the gallery and suppresses views of other artwork, the phrases mirror the psychological barriers we erect to avoid difficult knowledge. The work reveals how our internal knowledge operates structurally, blocking encounters with threatening or destabilizing ideas, histories, and realities. What appears as reasonable distance or honest ignorance becomes, through repetition and spatial enforcement, a mechanism of active refusal.

These Networks In Our Skin, 2023

Single-channel video

5:48 minutes, looped

Traditional Nigerian Igbo cosmology speaks of Ala, the goddess of the land, whose dominion includes everything on and buried within the ground, from crops to ancestors. In some areas of Igboland, any laments, desires, or problems in these domains required the construction of mbari works of art for Ala, in the hopes that she might hear those calls and intervene on behalf of those who sought her help.

In These Networks In Our Skin, Mimi Ọnụọha updates Igbo cosmological tradition to the present-day, enveloping the cables that run beneath the ground as a space under Ala’s dominion. In the short film, four women (whose faces remain obscured throughout the entire piece) collectively work to rewire the cables that carry the information that powers the world, filling them with materials of significance — dust, hair, spices — that draw on themes of ritual and collectively. Ọnụọha converts what could easily be mechanized labor into communal repair. The artist writes, “In much of my work I’m bringing forward different stories, rituals, and ways of being that can feed into new positionings and understandings of technologies. More often than not these new stories aren’t entirely new. They might consist in part of my own ideas, but often I’m simply clearing room for older rituals, stories, and ways of being that have been discarded along the paths of modernity, coloniality, and globalization.”

The short film offers a dreamlike visual lexicon of what it might mean to recreate the internet and more, starting from the philosophical, cultural, and relational values infused in the infrastructure that make it up.

This work is typically shown alongside The Cloth In The Cable.

Machine Sees More Than It Says, 2022

Single-channel video, color archival footage

3:47 minutes, looping

In Machine Sees More Than It Says, clips of footage are gathered from archival videos made between the 1950s and 1980s. Stitched together, they form a sketch of a computer's imagining of itself and the courses of development which formed it, hinting at processes of resource extraction, transport, technical advancement, interfaces and labor.

In the words of the artist: "I was working on a completely different piece and kept stumbling across footage from different videos that all seemed to share an aesthetic feel and hint at deeper computational stories....as if the tools I was using were intervening to speak of themselves.”

The Cloth In The Cable, 2023

Mixed-media installation

75 feet of cable with hair, spices, cloth, earth

In a dreamlike installation that draws on traditional Igbo cosmology, data cables are laced with culturally significant materials (spices, cloth, and soil), infusing them with new values. In the face of what Ọnụọha describes as “algorithmic violence” — the devastating impact on and exclusion of whole ‘categories’ of people inflicted by the calculations of automated decision-making systems — she conjures a whole new mythology to better govern the creation and maintenance of the technical infrastructure that connects the world. The artist states, “This work is an invitation for and invocation of different types of intelligence.”

Wherever The Cloth In The Cable is shown, Ọnụọha invites a local designer or practitioner to embellish the data cable installation with fabric, materials, and techniques that draw on their own personal heritage and narrative, weaving fabrics and textures into the work that recall the local context and foreground the primacy of our own bodily engagement with the world.

This installation is a gesture towards infusing modern technical systems with values and ontologies from past, different, and indigenous cultures, regions, people. This work is typically shown alongside These Networks In Our Skin.

This text adapted from the Australian Centre for Contemporary Arts

we don’t talk about that, 2025

Site-specific immersive installation

astroturf, green paint

In We Don’t Talk About That, viewers experience an immersive room installation covered entirely in artificial turf—walls, floor, and an irregular mound viewers can touch, walk around, and interact with.

The synthetic grass evokes the manicured surface of suburban order, where violence and erasure are buried underground. The work points to collective strategies of covering over and forgetting, reminding us that experiences left unspoken continue to shape the present.

everything you bury will come back up again, 2025

Set of 2 pigment inkjet prints

pictured with No One Told Me

In everything you bury will come back up again, Ọnụọha investigates the act of digging as both a physical gesture and a symbolic process. The photographs show hands sinking into soil, searching for traces. The ground appears dense and dark, as if holding on to history that lay concealed for years. Between the fingers lie a small sugar sack and a pair of hand-carved wooden dice—the first a tribute to forced labor, the second a reference to personal belongings. These modest objects convey closeness and individuality, standing in for the intertwining of exploitation and humanity, showing that even minimal material remains can open a window onto experiences that might otherwise have been erased.

The work emerges from the 2018 discovery of a mass grave in Sugar Land, Texas, containing the remains of 95 people—all casualties of convict leasing, a system in which mainly Black Americans were charged with false crimes so their labor could be sold to the highest bidder. Here, digging becomes a metaphor for bringing buried information to light. The work makes clear that engagement does not take place in the archive alone—it is an act of the eternal present, laced throughout our everyday gestures of approach, touch, and attention.

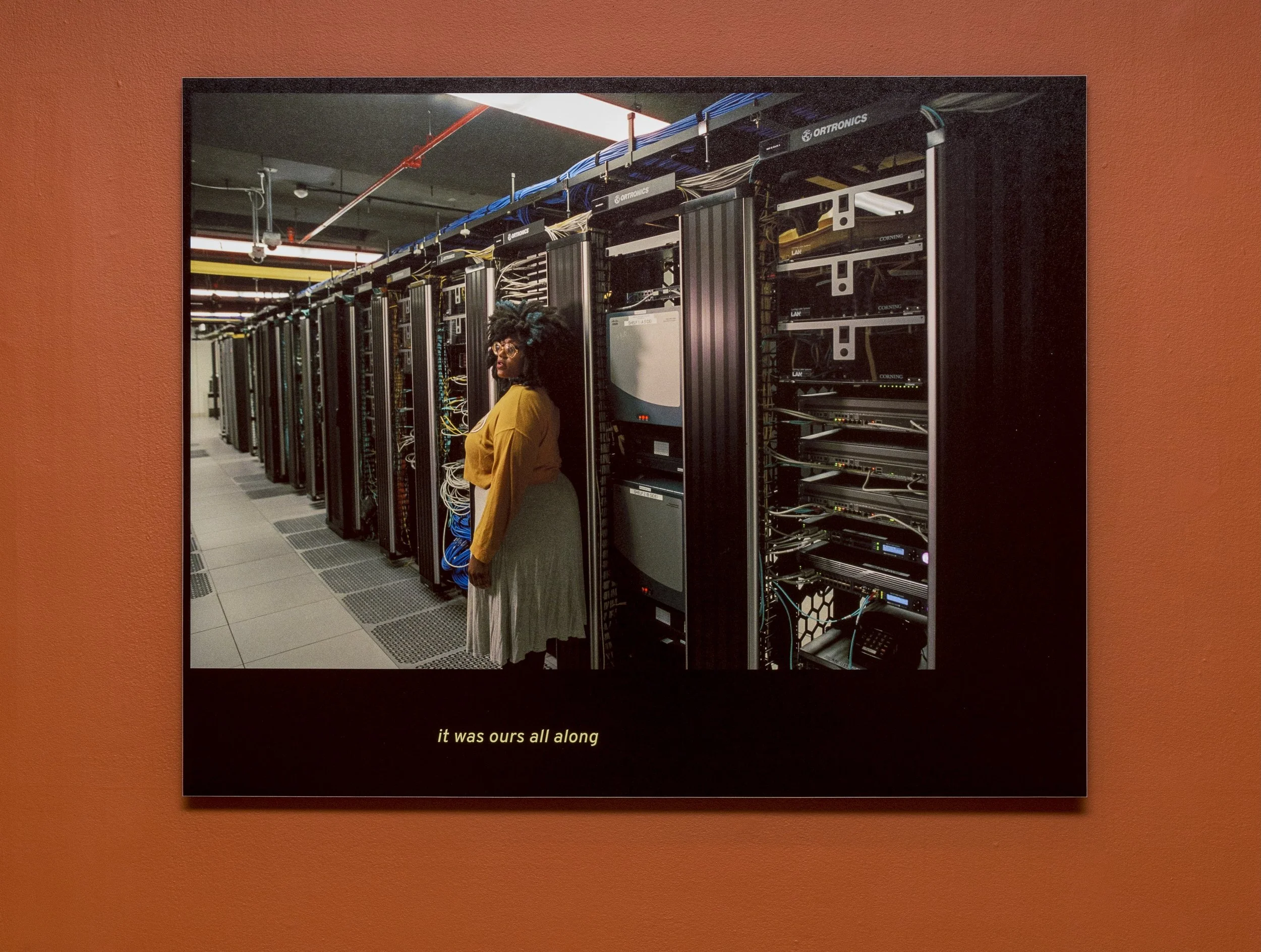

Natural: or Where Are We Allowed To Be, 2021

Large film photographic prints with captions

Natural is a photographic film series in conversation with British-Jamaican photographer Ingrid Pollard’s work Pastoral Interludes, in which Pollard cuts an otherwise idyllic depiction of black British subjects wandering a pastoral countryside with captions that hint at the danger of the act and darkly engage with the troubling realities of venturing outside of one’s imagined place.

The subject of Mimi Ọnụọha’s Natural: or Where Are We Allowed To Be is similarly out of place. In the series of three film prints, she is captured within a data center that holds her information within it; in the captions she reaches towards a desire to be author, not subject, of information that is in reach but out of her grasp.

This work is accompanied by an essay titled Natural that is published in the MIT Press anthology Uncertain Archives: Critical Keywords for Big Data.

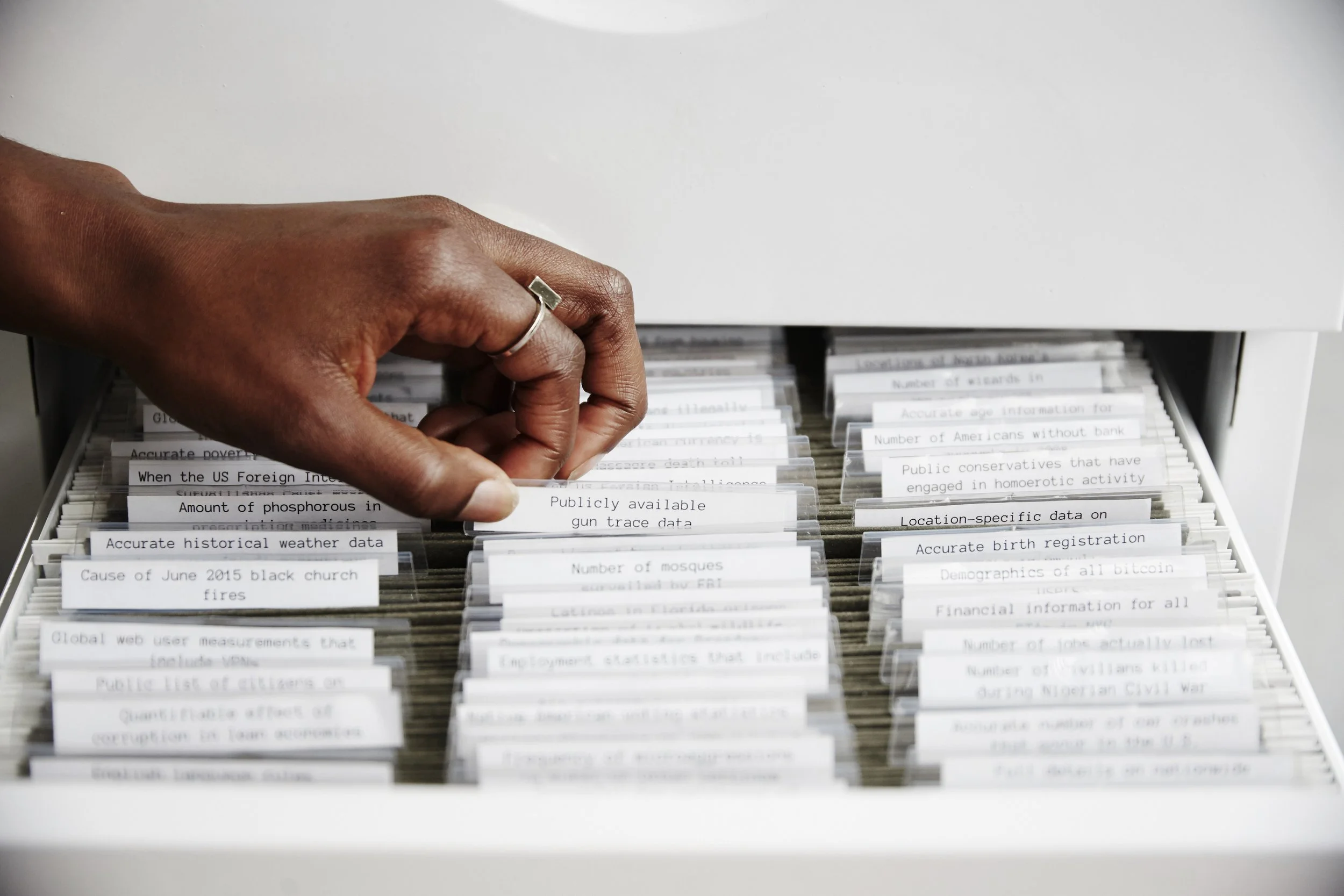

The Library of Missing Datasets (series), 2016 - ongoing

Installation of steel filing cabinets and folders

The Library of Missing Datasets (2015–ongoing) is a series of physical repositories that examine what is systematically excluded in our data-saturated society. The project maps the "blank spots" where information should exist but doesn't—absences that reveal cultural values and power structures more clearly than what we choose to collect.

The series begins with an ongoing archive of empty folders, each titled with a missing dataset drawn from a master list Ọnụọha has maintained since 2015. As the artist writes, "The word 'missing' is inherently normative; it implies both a lack and an ought: something does not exist, but it should." These absences disrupt established systems, offering cultural hints about what society deems important—or disposable.

The Library of Missing Datasets v2.0 narrows its focus to nonexistent datasets related to Blackness, addressing the paradox of Black people being over-represented in data collection yet systematically excluded from the processes of gathering and interpreting that data.

The Library of Missing Datasets v3.0 is a smaller, locked cabinet contains high-risk datasets whose very existence could endanger those entangled within them. By restricting access, the work confronts the paradoxically inverse relationship between transparency and protection, acknowledging that visibility can be both a tool of accountability and a weapon.

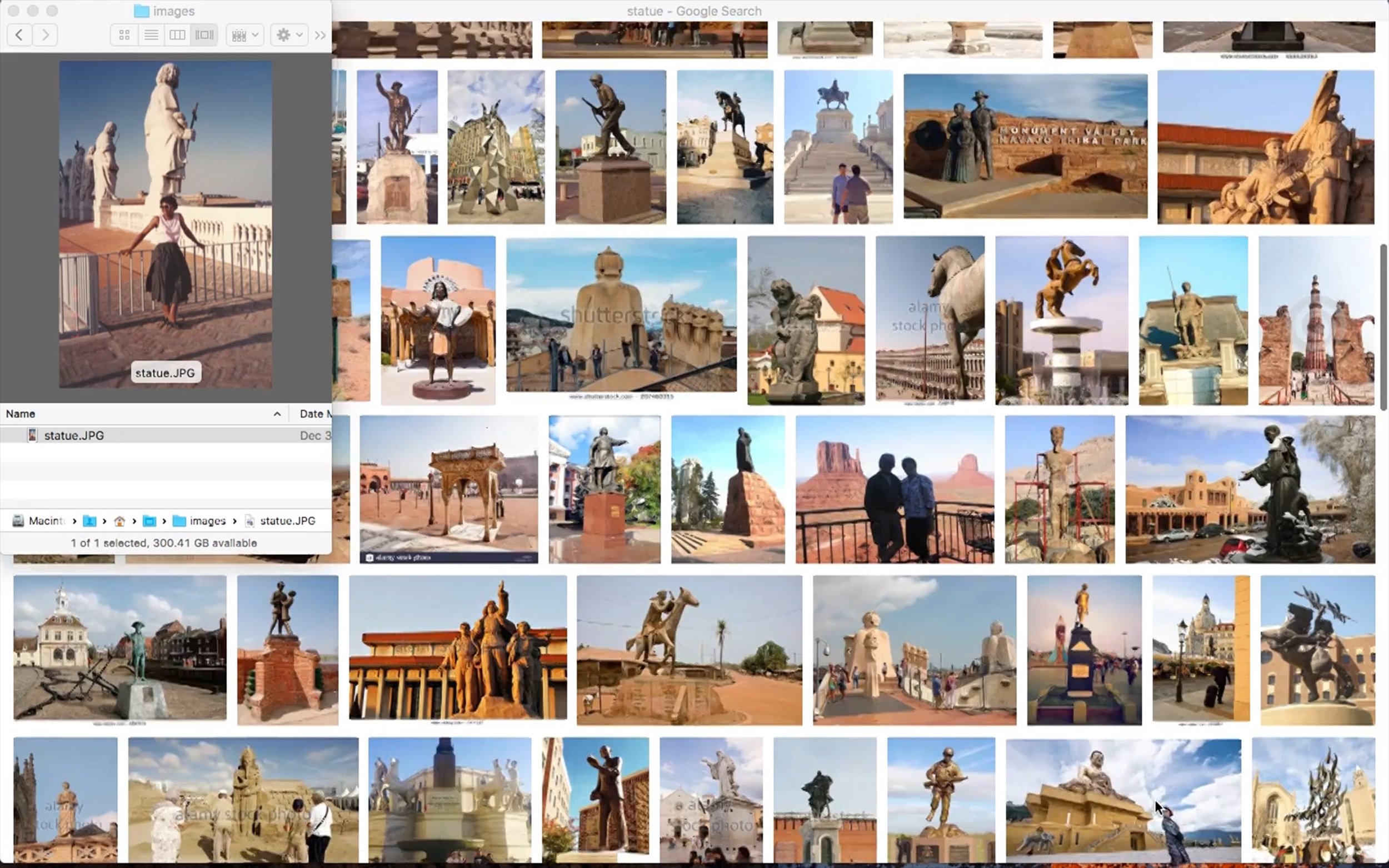

Us, Aggregated 3.0, 2019

Single-channel color video

15:41 minutes, looped

Us, Aggregated 3.0 suggests that the ability to unilaterally group others is an act of subtle but undeniable power. To categorize from above is, in the words of Donna Haraway, a way of “seeing everything from nowhere.”

This video piece presents a collection of photos from the artist’s family’s personal archive — photos that had never before been online — set alongside images that Google’s reverse-image search algorithms categorized as computationally similar to each archive photo. Attained by the artist programmatically querying and scraping Google’s image database, the images compose an aggregation of “us” that is effortlessly mediated by sophisticated machine learning algorithms to serve the needs of industry.

A mouse hovers over the images, further pulling viewers into the murky dynamics of classifying bodies. There is no “us”, only a “them.”

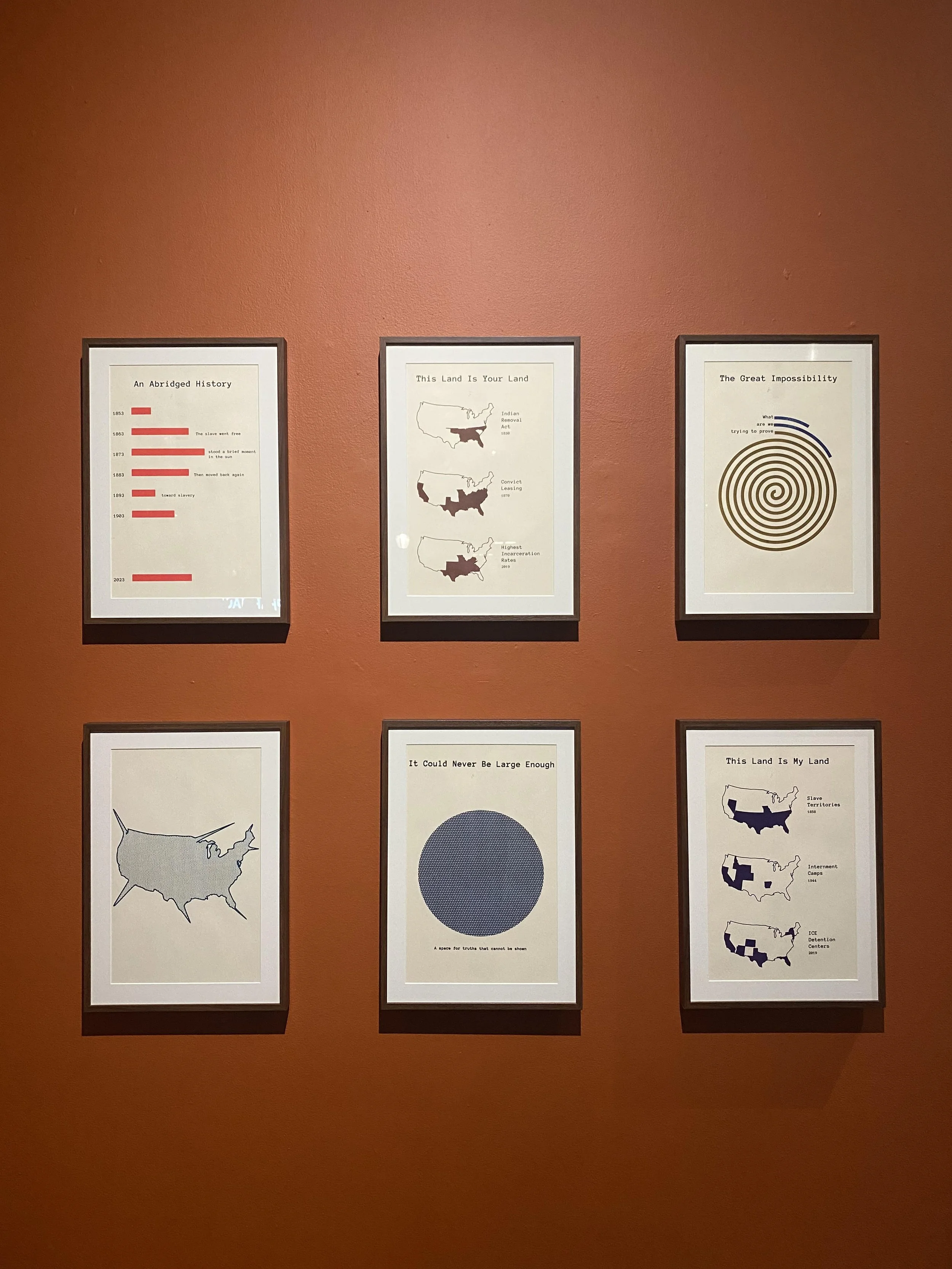

In Absentia, 2019

Print installation

six 11” x 17” risograph prints

In the early 1900s, sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois was asked by the US government to conduct research on black rural life in Alabama. The report he created was never published.

In In Absentia, Mimi Ọnụọha creates a series of risograph prints that begin from this removal and ask what happens when information is made to disappear by those who seek to obscure the intertwined workings of racism and power. The series of prints, which mimic Du Bois’ graphics, complicate assumptions about data’s veracity in both presence and absence.

40% of Food in the US is Wasted

(How the Hell is That Progress, Man?) 2023

Single-channel video, archival footage

color, sound

5:48 minutes, looped

Mimi Ọnụọha’s 40% of Food in the US is Wasted (How the Hell is That Progress, Man?) is an interactive video composed of archival video clips from the 1950s–1980s. Advertising the technological optimism of big agriculture, the sampled footage and audio betray the myth of agricultural systems geared towards ever-increasing production and yield rather than equitable distribution. Retrospectively, the videos function as a reality check to the solutions they once proclaimed.

The artwork’s title emphasizes the reality of food waste, referencing the USDA’s own damning estimate that 30–40% of food in the US is wasted. The presentation of the video clips in a repetitive grid formation advanced by continuous clicking amplifies the redundancies built into the process of automation. Ọnụọha ends the work with a repeated question: “How the Hell is That Progress, Man?”

Text adapted from text by Whitney museum curator Christiane Paul

The Future Is Here!, 2019

Single channel looping video

23:30 minutes

The Future is Here! complicates seamless narratives of technology by focusing on the sites where the process of creating massive datasets for machine learning begins: the homes of the people whose routine and tedious digital annotation makes the technology possible.

To create The Future is Here!, Mimi Ọnụọha joined the digital platforms of data annotation workers and asked workers to send photos of the places where they carried out their work. The artist then created stylized versions of these images that borrows from the tongue-in-cheek visual language of comic books and hand-drawn illustration to tease out the myth and reality of the labor behind machine learning. The two sets of photos are presented alongside each other in a custom-coded application by the artist, which is presented either as a website or video.